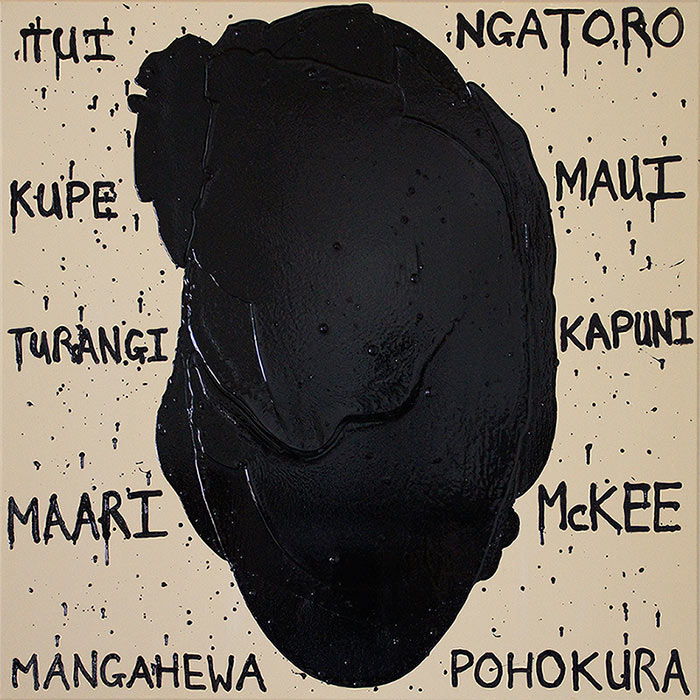

2016 National Contemporary Art Award Exhibition

My painting The Oil Fields (image below) has been included in the 2016 National Contemporary Art Award. The exhibition of the 34 finalists’ work has been on show at Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato since early September and ends soon, on 4 December.

The judge and curator for the award this year was Misal Adnan Yildiz, the current director of Artspace NZ. In his Judge’s statement Adnan noted that, “Today, from Orlando to Istanbul gender politics are still relevant. The questions around immigration, integration and refugees are urgent. ‘The end of neoliberalism’ is not just a title for an article printed by Monocle magazine; it is a reality that surrounds us. We are seeing the end of things and the new beginnings every day, every moment, every second, more and more… “, and ” I am proud that the exhibition of finalists for the 2016 National Contemporary Art Award is based on questions we can share with the rest of the world.”

I assume this sociopolitical inclination was a big part of the reason my work was selected from the hundreds of entries. My mandatory statement accompanying my entry (and printed on the label beside the work in the gallery) reads, “The Oil Fields lists names of active oil fields in Aotearoa, alongside a painterly depiction of a crude oil spill. The painting is part of an ongoing series recognising that in the early twenty-first century we are still fully immersed in the Oil Age.

Despite the emergence of the digital era, the exponential growth of renewable energy around the world, and escalating climate change, world oil consumption has continued to increase over recent decades.

We are drilling for oil deeper in the oceans than ever before, and extracting unconventional forms of oil such as shale oil and tar sands oil. It is inevitable that the Oil Age will come to an end as the world transitions to more sustainable forms of energy, but how long will it take?”

Overall, having work in the 2016 National Contemporary Award has been a really positive experience. I can’t say reading the largely negative EyeContact review by Peter Dornauf gave me much pleasure though. I’m not sure why EyeContact would choose a conservative critic to review such a show, but as I said in my social media, I’m claiming Dornauf’s trumped-up, derogatory labelling of my work: Neo-Casual Propaganda. It’s quite catchy.

Review: Vanessa Beecroft’s VB40 & John Johnston’s Face Value, 1999

Vanessa Beecroft’s VB40

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

August 4 and 5, 1999

John Johnston’s Face Value

Gallery 19, Sydney

July 21 to 31, 1999

By Ihor Holubizky

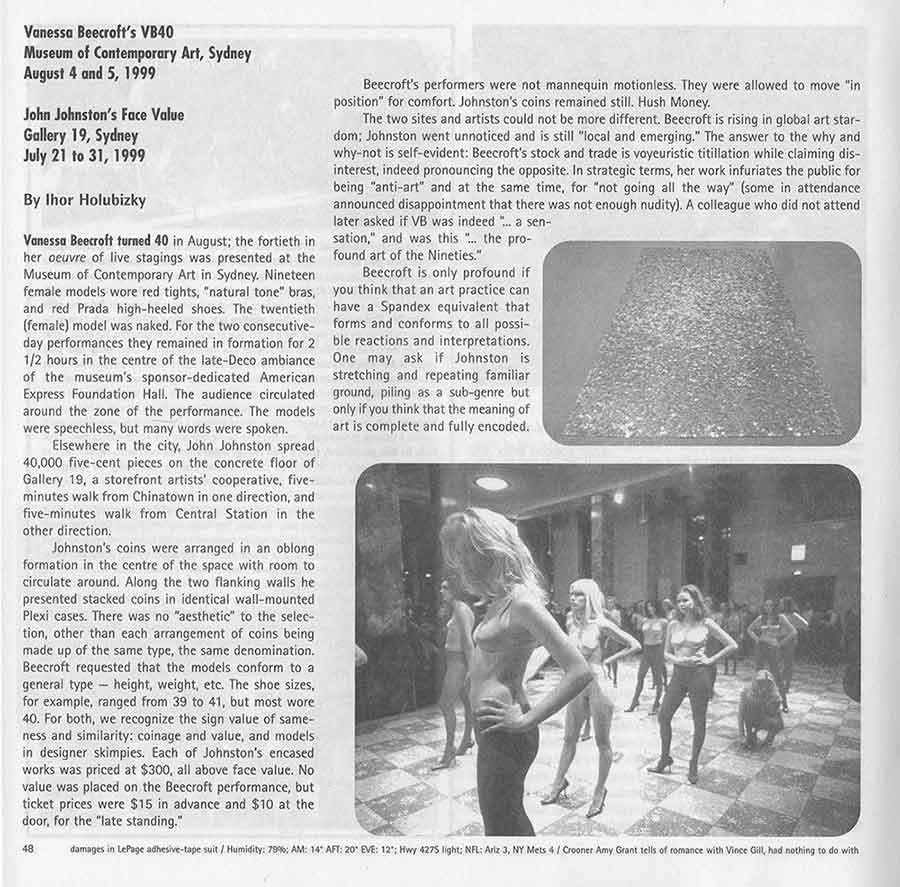

Vanessa Beecroft turned 40 in August; the fortieth in her oeuvre of live stagings was presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Nineteen female models or red tights, “natural tone” bras, and red Prada high-heelded shoes. The twentieth (female) model was naked. For the two consecutive-day performances they remained in formation for 2 1/2 hours in the centre of the late-Deco ambiance of the museum’s sponsor-dedicated American Express Foundation Hall. The audience circulated around the zone of the performance. The models were speechless, but many words were spoken.

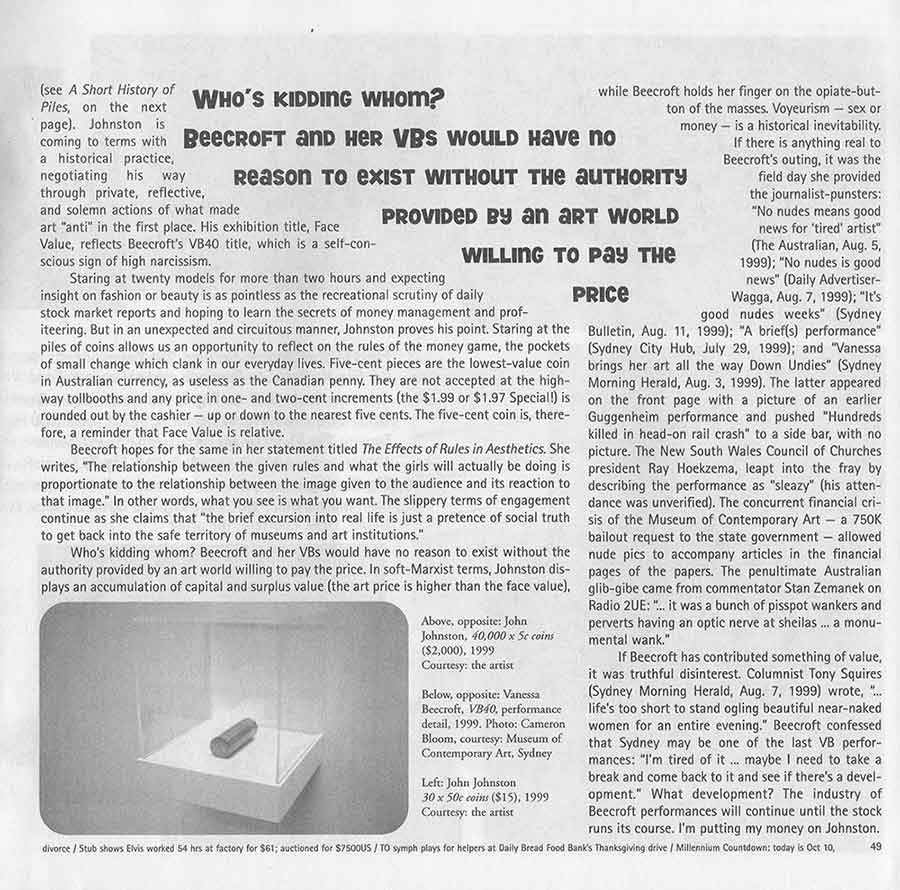

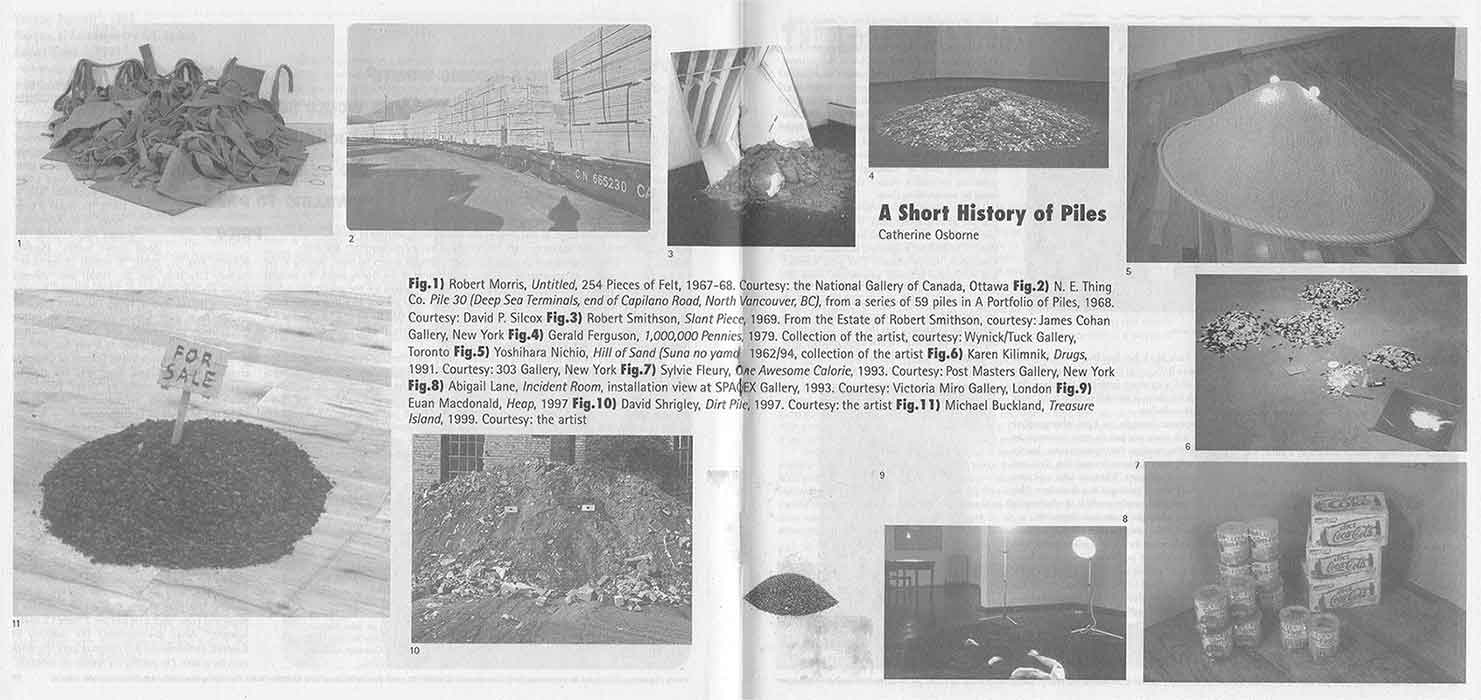

Beecroft is only profound if you think that an art practice can have a Spandex equivalent that forms and conforms to all possible reactions and interpretations. One may ask if Johnston is stretching and repeating familiar ground, piling as a sub-genre but only if you think the meaning of art is complete and fully encoded (see A short History of Piles, on the next page). Johnston is coming to terms with a historical practice, negotiating his way through private, reflective, and solemn actions of what made art “anti” in the first place. His exhibition title, Face Value, reflects Beecroft’s VB40 title, which is a self-conscious sign of high narcissism.

Staring at twenty models for more than two hours and expecting insight on fashion or beauty is as pointless as the recreational scrutiny of daily stock market reports and hoping to learn the secret of money management and profiteering. But in an unexpected and circuitous manner, Johnston proves his point. Staring at the piles of coins allows us an opportunity to reflect on the rules of the money game, the pockets of small change which clank in our everyday lives. Five-cent pieces are the lowest-value coin in Australian currency, as useless as the Canadian penny. They are not accepted at the highway tollbooths and any price in one and two-cent increments (the $1.99 or $1.97 Special!) is rounded out by the cashier – up or down to the nearest five cents. The five-cent coin is, therefore, a reminder that Face Value is relative.

Beecroft hopes for the same in her statement titled The Effects of Rules in Aesthetics. She writes, “The relationship between the given rules and what the girls will actually be doing is proportionate to the relationship between the image given to the audience and its reaction to the image.” In other words, what you see is what you want. The slippery terms of engagement continue as she claims that “the brief excursion into real life is just a pretence of social truth to get back into the safe territory of museums and art institutions.”

Who’s kidding whom? Beecroft and her VBs would have no reason to exist without the authority provided by an art world willing to pay the price. In soft-Marxism terms, Johnston displays an accumulation of capital and surplus value (the art price is higher than the face value), while Beecroft holds her finger on the opiate-button of the masses. Voyeurism – sex or money – is a historical inevitability. If there is anything real to Beecroft’s outing, it was the field day she provided the journalist-punsters: “No nudes means good news for ‘tired’ artist” (The Australian, Aug 5, 1999); “No nudes is good news” Daily Advertiser-Wagga, Aug 7, 1999); “It’s good nudes weeks” (Sydney Bulletin, Aug, 11, 1999); “A brief(s) performance” (Sydney City Hub, July 29, 1999); and “Vanessa brings her art all the way Down Undies” (Sydney Morning Herald, Aug. 3, 1999). The latter appeared on the front page with a picture of an earlier Guggenheim performance and pushed “Hundreds killed in head-on rail crash” to a side bar, with no picture. The New South Wales Council of Churches president Ray Hoekzema, leapt into the fray by describing the performance as “sleazy” (his attendance was unverified). The concurrent financial crisis of the Museum of Contemporary Art – a 750K bailout request to the state government – allowed nude pics to accompany articles in the financial pages of the papers. The penultimate Australian glib-gibe came from commentator Stan Zemanek on Radio 2UE: “… it was a bunch of pisspot wankers and perverts having an optic nerve at sheilas … a monumental wank.”

If Beecraft has contributed something of value, it was truthful disinterest. Columnist Tony Squires (Sydney Morning Herald, Aug 7, 1999) wrote, “ … life’s too short to stand ogling beautiful near-naked women for an entire evening.” Beecroft confessed that Sydney may be one of the last VB performances: “I’m tired of it … maybe I need to take a break and come back to it and see if there’s a development.” What development? The industry of Beecroft performances will continue until the stock runs its course. I’m putting my money on Johnston.

A Short History of Piles, Catherine Osborne

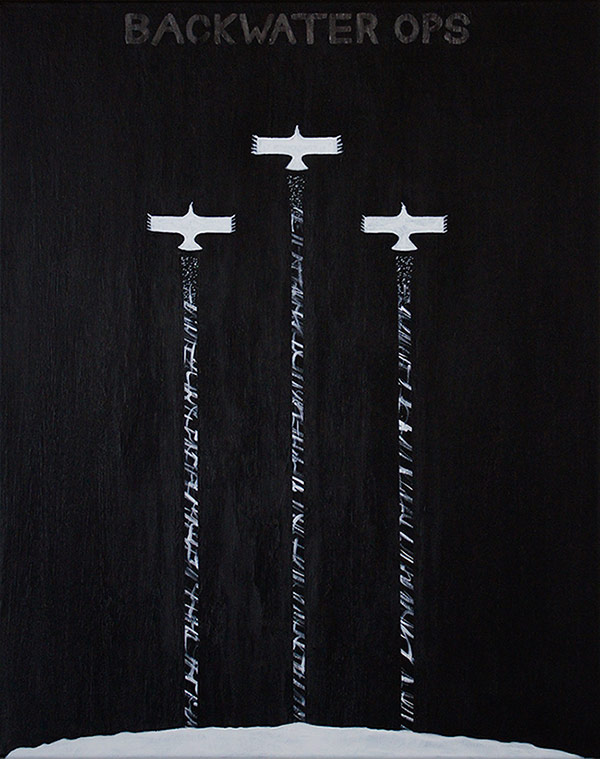

Notes on Backwater Ops Paintings

Below are some notes on ideas and influences associated with my recent Backwater Ops series. While not exhaustive, they represent some of my intentions and thoughts when making the work.

Backwater

Most viewers are unlikely to get this reference, but for me the series title Backwater Ops is partly a play on Blackwater, which was the name of a private military firm (later changed to Academi). Blackwater is also the title of a bestselling book about that secretive company, or rather mercenary army, by investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill. The book details how Blackwater became one of the most powerful players in the Iraq War, and in the ongoing War on Terror in many countries.

Scahill went on to co-found The Intercept with well known investigative journalist Glenn Greenwald and documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras. They were the people Edward Snowden entrusted to reveal his leaked NSA documents to a shocked world. These leaks revealed how the NSA, along with its international Five Eyes spy agency partners, including New Zealand’s GCSB, had in secret been building the largest and most pervasive infrastructure for mass surveillance the world has ever known.

More obviously than the Blackwater reference, I also chose the title Backwater Ops to allude to New Zealand’s involvement in this international spy alliance. No doubt New Zealand plays a small but important role in the five-country Five Eyes network, but it can be considered a backwater compared to the military intelligence might of the US and UK.

In social media I have jokingly referred to New Zealand as being at the very end of the internet, an internet backwater, but of course everyone online is now connected by mere moments, whatever their geographical location. Although internet communication is close to instant now, in an increasingly globalised world, including the art world, New Zealand can still be considered a backwater. It’s far away from the major “art centres” such as New York, London, and Berlin. However, although remote, a backwater can be used to create and hold important secrets, and to develop secret projects, out of view from prying eyes.

Post-Snowden

Like many people around the world, I was shocked to learn of Edward Snowden’s revelations about the Five Eyes alliance and its extensive, ever-growing surveillance capabilities. I was transfixed by the regular articles from The Intercept, mainly by Glenn Greenwald, and the world’s reactions to Snowden’s leaks. The internet has become a huge part of our daily lives, and the new knowledge that government spy agencies were using it to conduct mass surveillance worldwide made people realise that the supposedly democratic internet had changed dramatically; it had become militarised.

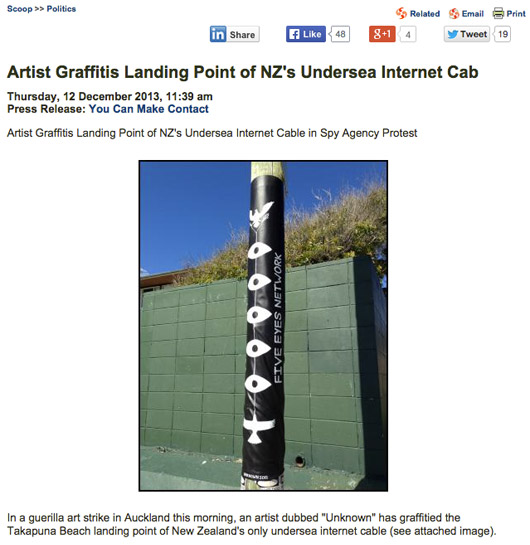

Immediately before my Backwater Ops series, in late 2013 and early 2014, when the public debate surrounding spy agencies and mass surveillance was in full swing internationally, I created a couple of works on the Five Eyes theme. These works included an outdoor guerrilla artwork at the landing point of New Zealand’s only undersea internet cable (see Five Eyes Network – Outpost and Five Eyes Network – Outpost). Snowden’s leaks had revealed the Five Eyes intention to tap the massive amount of data running through this Southern Cross cable. It was not clear how far that work had progressed, or if it had already being carried out. After the Snowden leaks, many assumed it was already happening.

Secret Military Patches

I want to mention the influence of the work of American artist, geographer, and author Trevor Paglan on my Backwater Ops series. Before making this work, I had read his book I Could Tell You But Then You Would Have to be Destroyed by Me. The book takes a look at the US military’s secret projects, which of course the rest of the world is not supposed to know anything about. Although top secret, it seems the military still creates identifying patches (worn on military uniforms) for these top secret ops.

Like my Backwater Ops paintings, these real military patches offer some cryptic clues about the nature of the classified projects they represent. The imagery is often aggressive, sinister, full of military bravado, yet often cartoonish. Paglan’s book documents a collection of more than 70 patches representing secret military projects, including secret weapons projects, intelligence operations, and secret aircraft squadrons. Often the patches use animal graphics, and of course nationalistic emblems.

These weird but real patches were partly a springboard for my approach to the Backwater Ops paintings. I began asking myself questions: as a Five Eyes partner, what if little Aotearoa New Zealand in the South Pacific also undertook top secret military projects, and produced imagery to do with these? What might that imagery look like? Further, what might the imagery look like if society took a distinctly dystopian path, where total surveillance and authoritarian rule became an everyday reality?

Backwater Ops is the result. It deals with an imagined, dystopian national identity. Like the real military patches Paglan collects, I’ve made use of some iconic national wildlife – tui, huia, tuatara, kiwi, kokako, ruru – as well as some other familiar national emblems and landscape imagery.

Wildlife and Environment

In the work, some of New Zealand’s iconic birds, the ancient tuatara, and an indigenous bat, have been transformed into authoritarian emblems representing a malevolent future. The Tui Elite Forces patrol a local landscape (Auckland’s Waitakere Ranges) like surveillance drones. The secret mission assigned to the native bat is to Collect All Signals All The Time. According to the classified NSA documents leaked by Edward Snowden, this is a stated goal of the NSA. In another work, a sinister, waspish emblem ominously states: Let Them Hate, So Long As They Fear. This well known quote is attributed to Roman Emperor Caligula and still surfaces from time to time in relation to tyrannical regimes and individuals.

The kōkako is heroically surviving Against All Odds. In this dystopian future, the struggling kōkako has been appropriated as an emblem of state and military survival. However, in Huia Forest Forces the (extinct) huia has had its military Operations Terminated.

The nocturnal and secretive ruru (or morepork) proclaims We Own The Night, and the prehistoric tuatara warns you to Keep Your Distance – as the public is cautioned to do in real life for reasons of conservation of the species. The secretive, and most iconic of all, kiwi bluntly announces in internet and texting shorthand that its Backwater Ops mission is simply NOYFB: None of Your Fucking Business.

New ‘Five Eyes Network’ Painting And ‘The Day We Fight Back’

Below is an image of my latest painting, Five Eyes Network. This new painting is similar to a recent guerilla art piece, Five Eyes Network, Surveillance Outpost, previously installed at the Takapuna Beach, Auckland landing point of New Zealand’s only undersea internet cable.

I’m sharing this new Five Eyes Network painting now to coincide with The Day We Fight Back against mass surveillance. Thousands of websites, including Reddit, Mozilla and Wikipedia are planning a massive protest on Tuesday, February 11th. I’m joining them with this website, my other site The9Billion, and with my various social media profiles.

Images of this painting are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License, so feel free to take a copy for yourself, and to share it with others. Larger, higher resolution images can be downloaded from my Flickr profile.

Review Of My Work In The Fringe

I’m happy to have had the following article written about my work for the September issue of local magazine, The Fringe. Thanks to Naomi McCleary for her interest in the work.

The Fringe, September 2013

Artist of the Month – John Johnston

John Johnston came to my attention as one of three Titirangi-based finalists in the inaugural Parkin Drawing Award, won by another Titirangi resident, Monique Jansen. The generous prize of $20,000 certainly brings focus to what judge Heather Galbraith describes as ‘one of our most ancient tools of communication, yet still incredibly relevant.’ The award attracted 800 submissions.

John Johnston creates work of mesmerising textural depth. His work for the Parkin Award, Signature Field 1, also has a fabric-like quality and a visit to his website (www.jjprojects.com) reveals wonderfully strong graphic images with delicate detailing. I particularly like his ‘Requiem for Hotere’ and works with more than a passing nod to McCahon’s waterfalls.

John has made a career as a digital designer, art director and social media consultant and is the founder of a popular sustainability-oriented blog, The9Billion.com. After his early years in Christchurch where he graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts (First Class Honours), he went on to complete a Master of Visual Arts (University of Sydney). In 2011 he returned from Australia and big city life to Titirangi, chosen for its long and strong legacy of artists and its proximity to bush and beach. With this move has come a return to making and exhibiting art and plans to continue this for the rest of his life.

Currently he is the generator of a ‘poster project‘ in which large paste-up images of one of his paintings, Downfall, based on McCahon’s waterfalls, are appearing on walls and billboards in deconstructed and reassembled collages. This is guerilla art at its best; temporary, intriguing, leaving no trace. For John, this project takes his work outside the gallery scene and into a non-arts domain. Further ideas to work in public space are emerging.

John Johnston is but one of a new generation of artists drawn to Titirangi. For the early artists who made their homes in these hills, it was often an escape from a judgmental and unrelenting society. Today’s artists come for its physical beauty and sustaining arts tradition and culture.

Naomi McCleary