Vanessa Beecroft’s VB40

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

August 4 and 5, 1999

John Johnston’s Face Value

Gallery 19, Sydney

July 21 to 31, 1999

By Ihor Holubizky

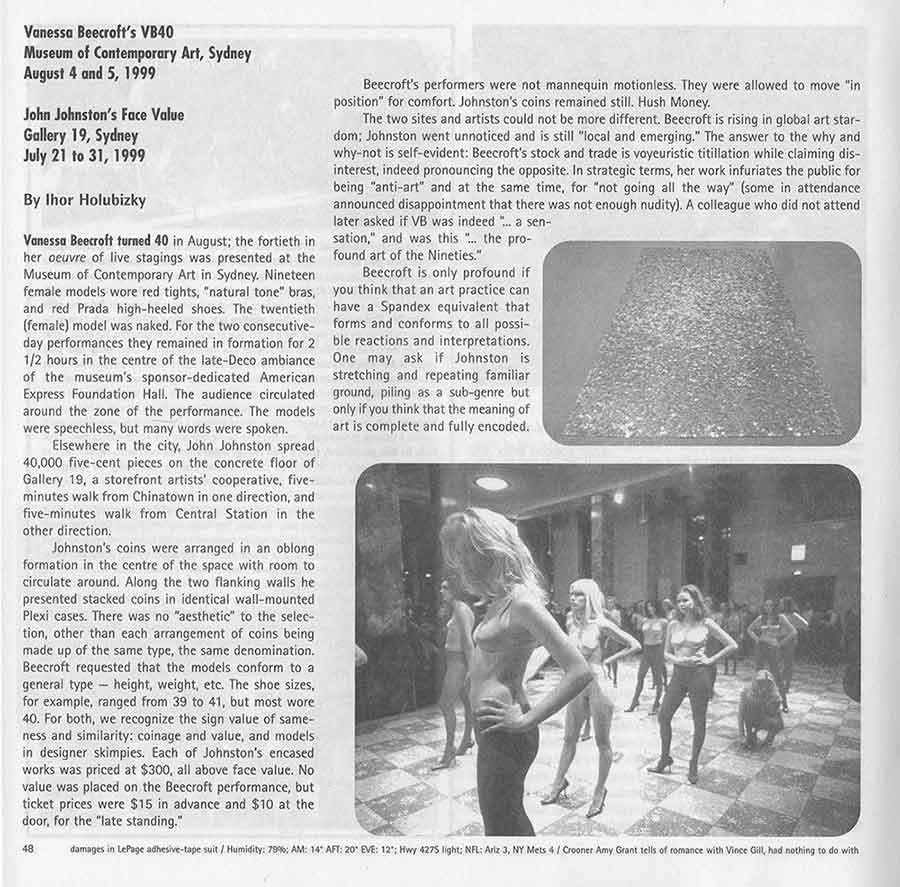

Vanessa Beecroft turned 40 in August; the fortieth in her oeuvre of live stagings was presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Nineteen female models or red tights, “natural tone” bras, and red Prada high-heelded shoes. The twentieth (female) model was naked. For the two consecutive-day performances they remained in formation for 2 1/2 hours in the centre of the late-Deco ambiance of the museum’s sponsor-dedicated American Express Foundation Hall. The audience circulated around the zone of the performance. The models were speechless, but many words were spoken.

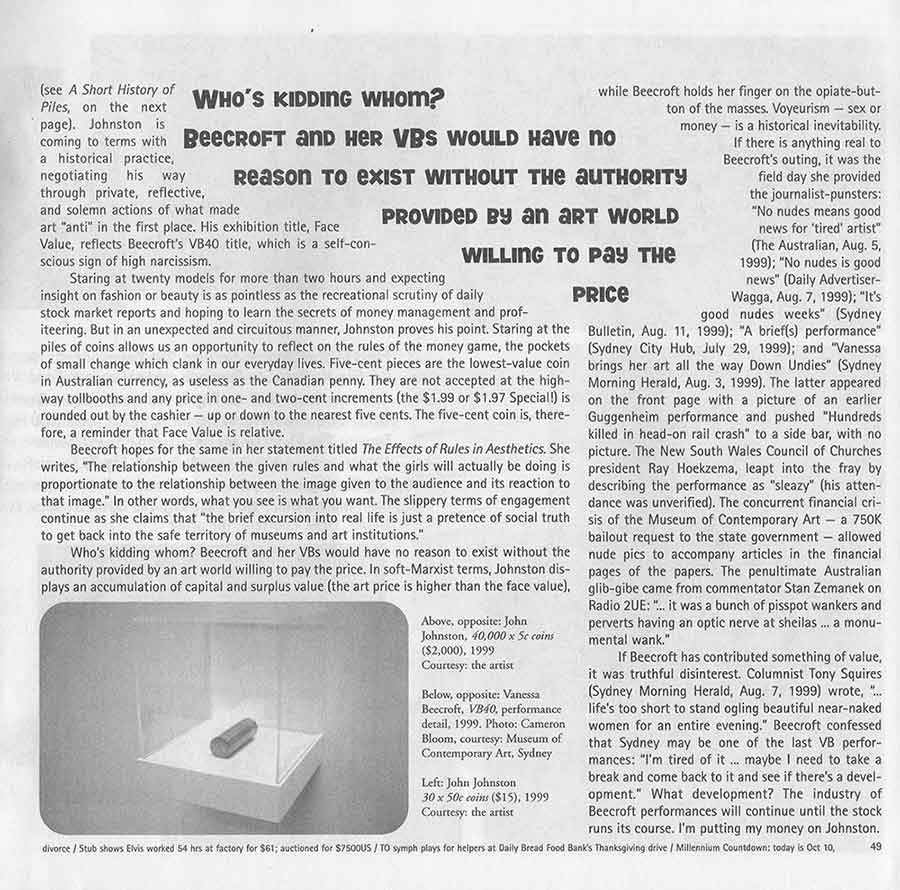

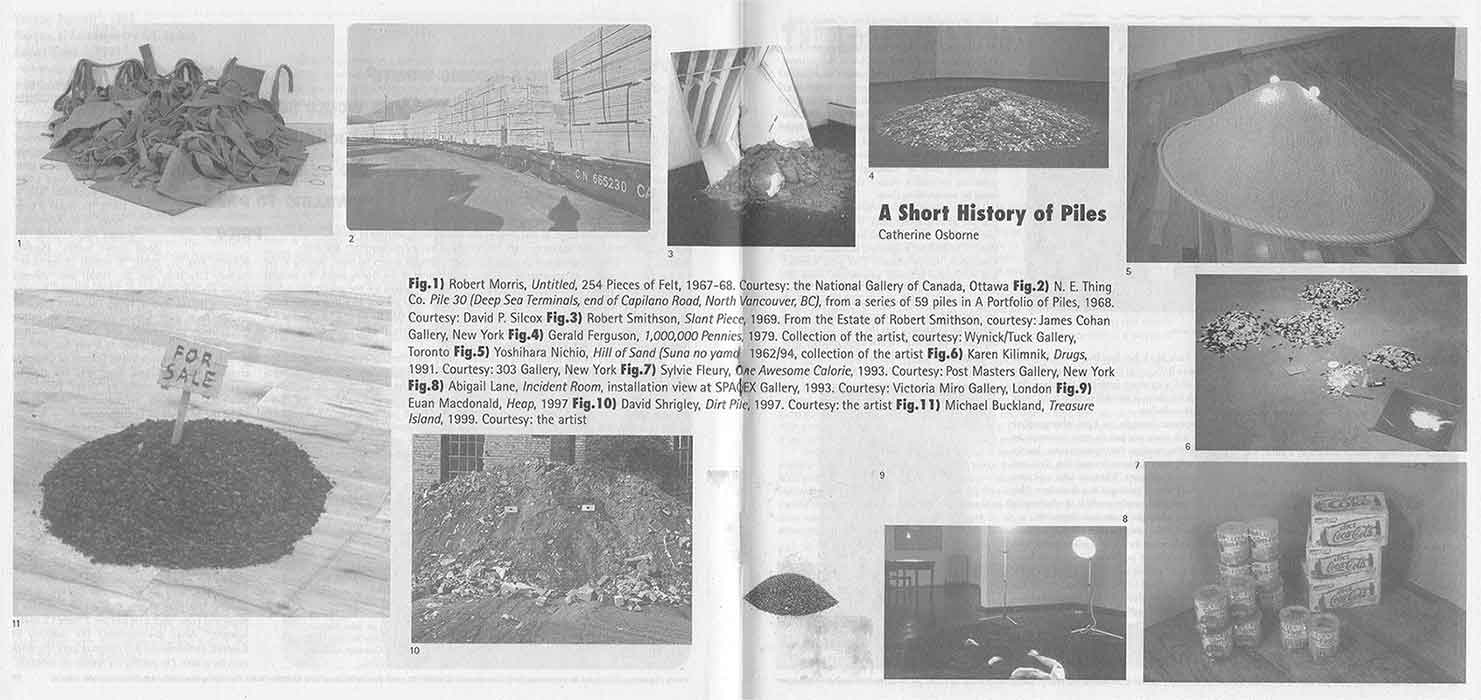

Beecroft is only profound if you think that an art practice can have a Spandex equivalent that forms and conforms to all possible reactions and interpretations. One may ask if Johnston is stretching and repeating familiar ground, piling as a sub-genre but only if you think the meaning of art is complete and fully encoded (see A short History of Piles, on the next page). Johnston is coming to terms with a historical practice, negotiating his way through private, reflective, and solemn actions of what made art “anti” in the first place. His exhibition title, Face Value, reflects Beecroft’s VB40 title, which is a self-conscious sign of high narcissism.

Staring at twenty models for more than two hours and expecting insight on fashion or beauty is as pointless as the recreational scrutiny of daily stock market reports and hoping to learn the secret of money management and profiteering. But in an unexpected and circuitous manner, Johnston proves his point. Staring at the piles of coins allows us an opportunity to reflect on the rules of the money game, the pockets of small change which clank in our everyday lives. Five-cent pieces are the lowest-value coin in Australian currency, as useless as the Canadian penny. They are not accepted at the highway tollbooths and any price in one and two-cent increments (the $1.99 or $1.97 Special!) is rounded out by the cashier – up or down to the nearest five cents. The five-cent coin is, therefore, a reminder that Face Value is relative.

Beecroft hopes for the same in her statement titled The Effects of Rules in Aesthetics. She writes, “The relationship between the given rules and what the girls will actually be doing is proportionate to the relationship between the image given to the audience and its reaction to the image.” In other words, what you see is what you want. The slippery terms of engagement continue as she claims that “the brief excursion into real life is just a pretence of social truth to get back into the safe territory of museums and art institutions.”

Who’s kidding whom? Beecroft and her VBs would have no reason to exist without the authority provided by an art world willing to pay the price. In soft-Marxism terms, Johnston displays an accumulation of capital and surplus value (the art price is higher than the face value), while Beecroft holds her finger on the opiate-button of the masses. Voyeurism – sex or money – is a historical inevitability. If there is anything real to Beecroft’s outing, it was the field day she provided the journalist-punsters: “No nudes means good news for ‘tired’ artist” (The Australian, Aug 5, 1999); “No nudes is good news” Daily Advertiser-Wagga, Aug 7, 1999); “It’s good nudes weeks” (Sydney Bulletin, Aug, 11, 1999); “A brief(s) performance” (Sydney City Hub, July 29, 1999); and “Vanessa brings her art all the way Down Undies” (Sydney Morning Herald, Aug. 3, 1999). The latter appeared on the front page with a picture of an earlier Guggenheim performance and pushed “Hundreds killed in head-on rail crash” to a side bar, with no picture. The New South Wales Council of Churches president Ray Hoekzema, leapt into the fray by describing the performance as “sleazy” (his attendance was unverified). The concurrent financial crisis of the Museum of Contemporary Art – a 750K bailout request to the state government – allowed nude pics to accompany articles in the financial pages of the papers. The penultimate Australian glib-gibe came from commentator Stan Zemanek on Radio 2UE: “… it was a bunch of pisspot wankers and perverts having an optic nerve at sheilas … a monumental wank.”

If Beecraft has contributed something of value, it was truthful disinterest. Columnist Tony Squires (Sydney Morning Herald, Aug 7, 1999) wrote, “ … life’s too short to stand ogling beautiful near-naked women for an entire evening.” Beecroft confessed that Sydney may be one of the last VB performances: “I’m tired of it … maybe I need to take a break and come back to it and see if there’s a development.” What development? The industry of Beecroft performances will continue until the stock runs its course. I’m putting my money on Johnston.

A Short History of Piles, Catherine Osborne